DXers use to distinguish between very rare, rare, semi-rare, and

everyday DX. This has nothing to do with distance, but refers to the

availability of the DXCC entity concerned. Stations from the US,

Japan, Brazil, South Africa, most European countries and many others

can easily be heard and contacted every day - they are sort of

noname DX. The overwhelming majority of radio amateurs belong to

this category. Nothing special - not really "needed", grey mice in

the DX circus. A country, however, in which no amateur radio

licences are issued (mostly for political reasons) or a remote

island somewhere in Antarctica or in the Pacific, belong to the

"very rare" or "rare" category; spots like them will be ranking very

high, maybe on top of the

Most-Wanted Lists

The

DX-Quickie - QSO-Patterns for the Different Modes

A

routine contact between an everyday station and a DX station

exchanging reports, names, locations (QTH) etc would take about ten

minutes - much too long if thousands upon thousands are impatiently

queuing for a long-hoped-for contact. The solution is to reduce the

length of the QSO to a tolerable minimum, e. g. to reduce it to the

exchange of signal reports (RS, RST, or RSQ) and a short

confirmation procedure, to be sure to be "in the log". The signal

reports exchanged - always a "59" (in telephony) or a "599" (in all

other modes) - are anything but "honest" or reflecting true signal

strength. Treat them as a pure placeholder without any informal

value. Ultra-short DX-QSOs of this category - let's call them

"DX-quickies" - differ a little from mode to mode, but with

experienced DX-operators they will always take only a minimal

fraction of the time of the routine QSO mentioned above. You may

download a pdf-file showing the spelling alphabet and tables with

the RST- and the RSQ report systems

here.

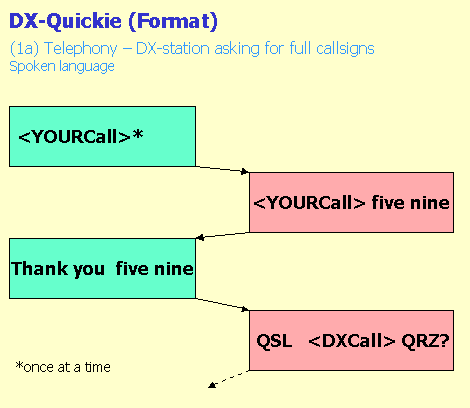

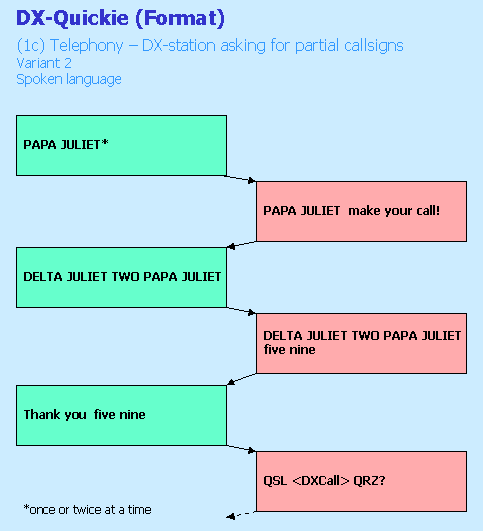

In

the boxes below, you'll find the patterns (formats) of typical

DX-quickies in the different modes (telephony, telegraphy, RTTY

including the Digimodes). The pink rectangles contain the texts which

the rare DX (<DXCall>) sends, the green rectangles contain the texts

of the station contacting the rare DX (<YOURCall>). You should

replace <YOURCall> by your personal callsign.

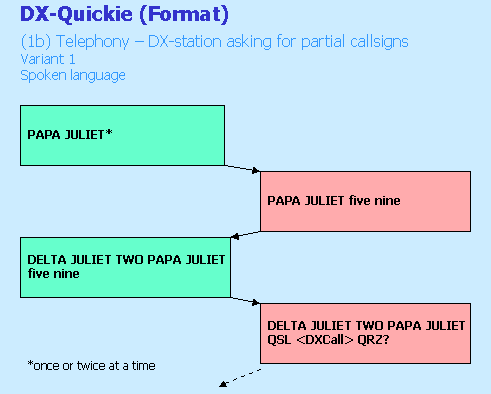

If a

DX-station asks for or accepts to be called with partial callsigns

(preferably the last two letters of the suffix), you should make use

of the following formats (assumed <YOURCall> = "DJ2PJ"):

In

case the DX does not follow the above pattern and verifies the full

callsign before giving a report, the following alternative format is

used:

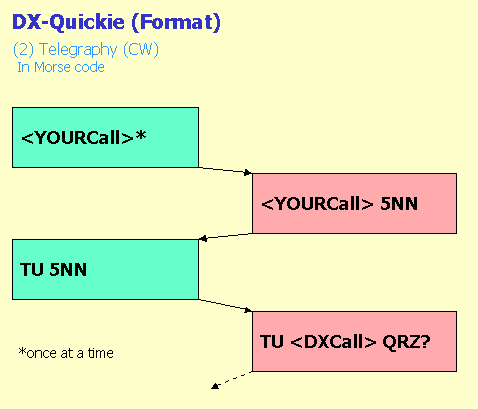

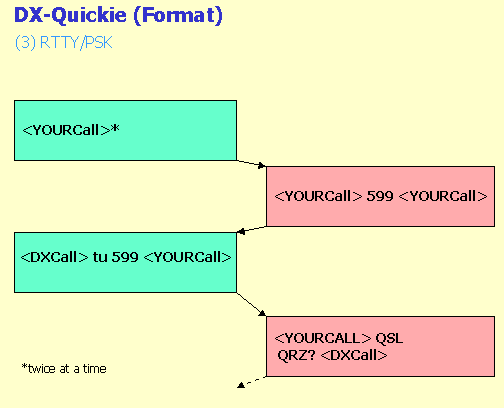

The

following two patterns - for telegraphy (CW) and RTTY/Digimodes -

are self-explaining. I recommend you to adopt the texts in the

green rectangles as macros for your CW-keyer and/or for the computer

programmes in use. Please note that in CW "599" is always (!) keyed

in an abbreviated form as "5NN", or even "ENN"!

In

RTTY, it is advisable to insert a <CR> (carriage return) at the

beginning of each transmission to improve synchronization of the

signal. Please note that - in contrary to RTTY - PSK (and some other

digital modes) are case-sensitive (divide between lower and upper

case letters)

Breaking through the Pile-Up

Operating with

one of the quickie-formats shown above is a perfect method to

considerably reduce the length of a contact and thus opening up a

lot more hams the chance to working the rare DX. On the other hand,

it does in no way solve the problem of too many stations calling on

the same frequency at the same time and making all or most signals,

including the DX-signal, unreadable for everybody.

The

magic formula for a way out of this dilemma is called "working

split": The DX-station is operating on one frequency, the callers on

another frequency or, preferably, on a multitude of frequencies

within a certain frequency range, in both cases keeping an offset

(QSX) of at least one or more kilohertz from the DX-station's

frequency. The idea is that the DX-station's

frequency remains free of callers, so that the DX can be heard "in

the clear". The rare DX will announce how many kHz offset (up or

down, higher or lower) from its working frequency (QRG) it will

listen for calls. Typical announcements are (in brackets: how you

should react):

in SSB (telephony):

"listening 5 to 10 up"

(= call him on any frequency between 5 and 10 kHz higher than his

operating frequency)

"listening 250 to 270"

(= call him on any frequency between x250 and x270 kHz, where "x"

stands for the band frequency, e. g. "14" for the 20-metre band; in

such a case: 14250 and 14270 kHz)

in CW

(telegraphy):

"2

up" (= call him exactly 2 kHz higher than his QRG or: call him at

least [!] 2 kHz higher than his QRG)

"2/5

up" (= call him between 2 to 5 kHz higher than his QRG or: call him

2 or 5 kHz higher than his QRG alternatively [!])

"35"

(= call him on exactly x035 kHz, where "x" stands for the band

frequency, e. g. "28" for the 10-metre band; in this case: 28035

kHz) - rarely used

"1

dwn" (= call him exactly 1 kHz lower than his QRG or: call him at

least [!] 1 kHz lower than his QRG) - down-offsets are rarely used

in RTTY (radio

teletype):

"3

up" (= call him exactly 3 kHz higher than his QRG or: call him at

least [!] 3 kHz higher than his QRG)

"up

up up spread out" (= call him at least 1 kHz higher but better use

a [much] higher offset [up to 10 and more kHz, depending on the

extent of the pile-up])

In

other modes, split operation is rarely necessary. In PSK, the

pattern mostly follows that of RTTY, although the split is not that

wide, and offset frequencies are usually expressed in Hz instead of

kHz.

If

a DX-station announces split operation without telling how much

offset is wanted ("up" or "dwn"), try to find out its

listening habits. Start with at least 1 kHz up and adjust your

offset appropriately

(see

the remarks on pile-up strategies below).

Let

me make a few remarks now on your transceiver. For efficient

split-frequency operation your transceiver has to provide at least

four facilities: two VFOs (A and B), a SPLIT-button that activates

the sub VFO for transmitting (listening with main VFO A,

transmitting with sub VFO B), an "A/B-reverse"-button that exchanges

the frequencies of VFO A and VFO B (to be able to listen on the

frequency you have chosen for transmitting), and - not that

necessary, but very wishful - an A=B-button which transfers the

frequency of VFO A to VFO B (to have identical frequencies on both

VFOs). This may sound a bit complicated, but you will easily

understand the functionality of the two VFOs and the different push

buttons as soon as you try them out yourself. I recommend some "dry

practice" before plunging into a real pile-up.

Imagine, while searching for CW-DX on 20 metres, you come across a

huge pile-up of fiercely calling stations. The pile has its peak at

about 14023 kHz, but reaches from about 14021 to 14026. You don't

know whom they are calling. Here is sort of a recipe (there are many

others...) for how to proceed:

("Aha!

There he is, on exactly 14020! His callsign ZK3XX, Tokelau

Island in the Pacific. Nice DX, but very weak, nearly

unreadable. Oh, well, the yagi is pointing into a south-westerly

direction. Completely wrong that; it should be 1° from this QTH,

that's near-exactly to the north!")

OK, turn your antenna to 1°

("Much

better signal now, peaking S5 to 6, no problem to read! ZK3XX

says: '2 up!'")

Press the A=B-button to have both VFOs on 14020

("Done!")

Adjust VFO B to 14022

("VFO

B on 14022 now")

Press the SPLIT-button to be able to transmit on 14022.

Carefully control if SPLIT is really on!

("SPLIT is

on!")

("OK!")

Follow this procedure enough times to find out where ZK3XX is

listening and working the other station(s). Does he really work

stations on just exactly 14022 (2 up from 14020, as he said)?

If not, what is his operating method? Is he slowly "drifting" up

in reception every or every two, three, four... QSOs? What is

his highest offset from 14020? Is he then moving down again?

To which frequency? Find the operation pattern!

("OK!

He worked OK2PAY on 14022, then S59A on the same QRG. Next was a

JA on a frequency slightly higher, then another JA on 14023. He

moves higher in frequency every 2 to 5 QSOs. The pile-up is

following him. If it gets too tough, he moves slightly higher:

0.5 kHz or a bit more... Highest frequency while on the way up

seems to be a little more than 14025, lowest frequency on the

way down seems to be little less than 14022. That's the spectrum

where I should call him. Good idea to call him 1 kHz higher than

he is working stations at the moment?")

OK, fine! As soon as ZK3XX listens, give him a call: just your

callsign - nothing else, not more than just one (!) time (see

the DX-Quickie pattern for CW above!)

("Sh...,

ZK3XX answers HA5FM, then QRZ again...")

OK, call again: same frequency, same sort of call. Regularly

check where he is picking flowers: with the A/B-reverse-button.

Adjust your transmitting frequency appropriately. Call him,

again and again.

("Yippee,

that's ME now! I finally got him!")

Fine, but don't forget to give him something to chow ("tu 5NN";

see the pattern above!)

("He

said 'tu', everything's fine now!")

That was perfect! Congratulations!

Please, do not expect to be as successful that soon as in our

example. In extreme pile-ups with hundreds or even thousands

calling, it can take hours, sometimes days, before it's your turn to

work the rare DX. Don't be too sure that the above strategy will help

you in all situations. Observe the DX-station's pattern of operation

very, very carefully, and try to be the right key in the lock; try

another key if one fails. Do not get angry or frustated at any

point; never really give up. Be self-confident enough to take a long

break if anger and frustration begin to gnaw. Why not work the

DXpedition one or two days later with a new shot of

adrenaline, why not contact them even one day before they leave the

rare spot when the pile-ups have calmed down?

We

haven't talked yet about one of the worst symptoms of working

pile-ups: deliberate jamming (QRM) on the DX frequency. Amateur

radio, radio amateurs are a part of society; they, too, reflect our

community as it is today. Aggressive persons, people with noticeable

mental deficits, neurotics maybe, belong to everyday life:

disagreeable neighbours, spiteful colleagues and other awkward

customers. It would border on the miraculous if they would not show

up in amateur radio as well. And there they are, in the pile-ups and

on traditional DX frequencies: people who do not really want to work

the DX but have decided to spoil all others' pleasure, for whatever

reason or even for no reason. Their anonymity - they will very

rarely reveal their callsign - seems to make them unassailable.

Really unassailable? Maybe, but there is a remedy though: simply

ignoring them, not showing any reaction whatever they come out with.

Believe a psychologist: Nothing hits and hurts these people more

than plain ignoration! Never try to educate them - they need therapy

(which you cannot provide...), not education.

Astonishingly, the reverse of the medal of working split is almost

never discussed or maybe even perceived: Whenever a rare DX station

initializes a split operation, neither the DX itself nor the

sometimes thousands of callers do not give a tinker's cuss about the

fact that without any warning all on-going QSOs in a large spectrum

above (or sometimes below) the DX station's frequency are brutally

massacred. There is no doubt that this not only is inconsiderate

behaviour but an incredible violation of what we all place value on,

the much-heralded Ham Spirit. Amazingly enough, you'll not find this

grievance even ventilated in one of the many DX codes of conduct...

Just another example for Jellineks "normative Kraft des Faktischen"

(normative power of the factual)?

Last-not-least: two simple rules - very important and yet easy to

follow. (No BUTs, please!)

NEVER,

really NEVER...

...transmit on the DX-station's frequency when in

SPLIT mode

...

react to people

deliberately or undeliberately jamming

...answer to questions

on the DX-station's frequency. Not the slightest remark or question yourself!

Regularly check if

SPLIT is set

on your transceiver!

In

addition to what I told you:

BEFORE

you join your

first pile-up (or go on your first DXpedition!),

PLEASE

read the

following:

DX Code of Conduct

ON4WW's "Let's make DXing

enjoyable again. Please!"

K7UA's "The New DXer's

Handbook"

(pdf-file)

The "DX University"

DL4TT's "Dawg X-ray Club"